Millennials and technology – busting the myths

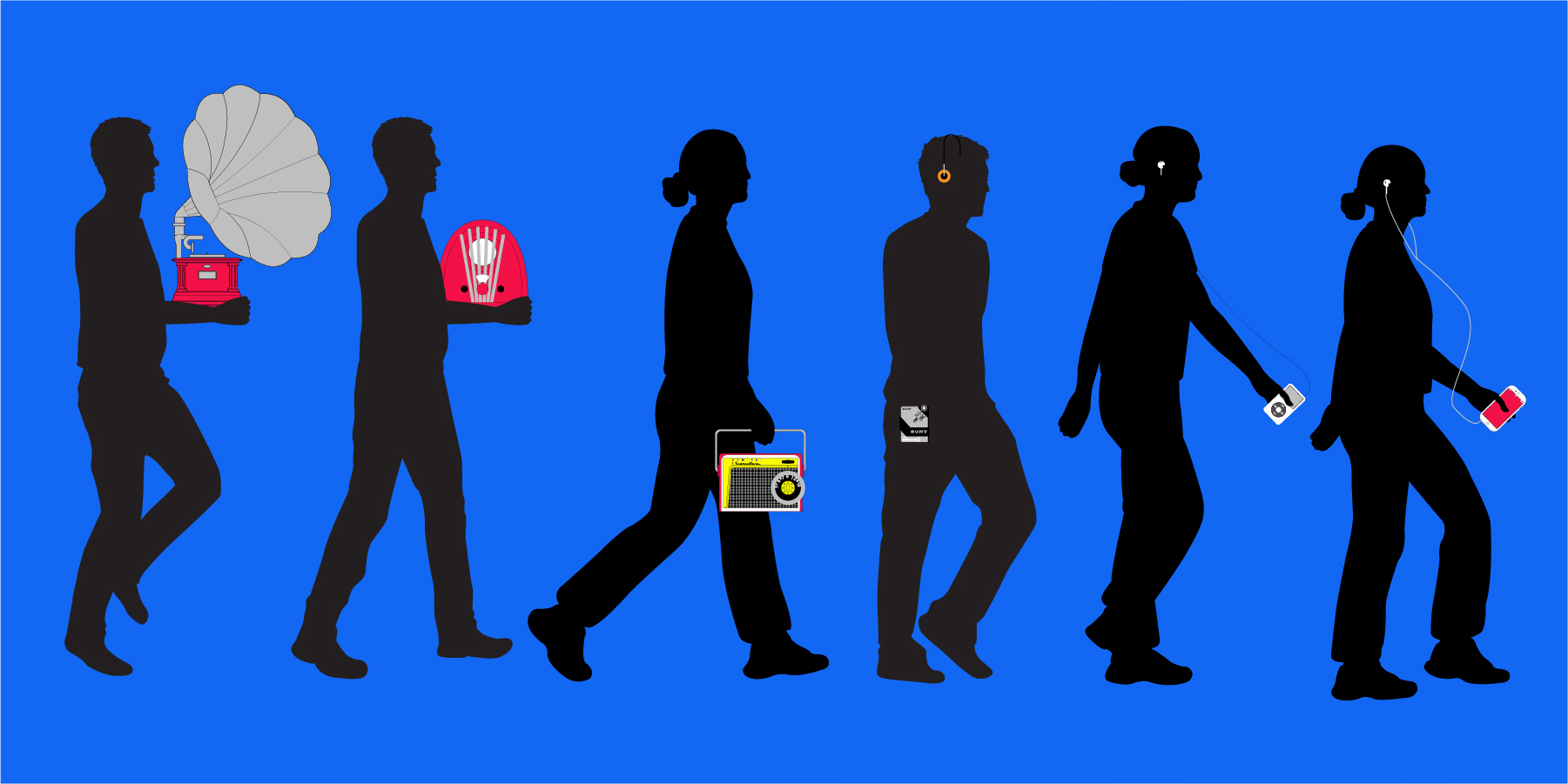

For the first time in history, five generations are working side by side. People who spent their teenage years dancing on the beach around a tinny transistor radio chat at the water cooler with coworkers who got their first smartphone at the age of ten.

The media would have us believe that each generation has its own particular traits. When generations mix, the clash of values and attitudes leads to conflict. Major historical events shape generations, and everyone is marked for life by the prominent technology of their youth.

Major historical events shape generations, and everyone is marked for life by the prominent technology of their youth.

Names and labels for generations vary, with some generations named after the technology or cultural phenomenon which supposedly shaped them. Gen X are known, somewhat disparagingly, as the MTV generation. The current target of much negativity, the millennials, are called digital natives, while their younger peers are the Net generation. How true is it that technology determines our character?

Technology has definitely changed the way we work rest and play, and this change has happened very quickly over the last hundred or so years. One example of this is the way we entertain ourselves.

The advent of the record player enabled people to listen to professional musicians and voice actors in the comfort of their own homes, which was much more fun than Aunt Dorothy’s rendition of Come into the Garden, Maud. You could listen to what you wanted when you wanted, although content was expensive. Radio then brought a constant stream of entertainment into the home, as well as an instant source of news for the first time. Record-player sales slumped as, bucking the coming trend, consumers preferred free content even if that meant broadcasters deciding what they listened to when.

Television brought sights as well as sounds and the profusion of channels in some countries heralded a greater range of choice. At the same time, small, cheap, battery-powered transistor radios added two new factors to the equation: portability and individualisation. Teenagers retreated to their rooms and listened to exciting new music that defined their generation. The songs they heard prompted them to run out to buy the record, to play on their own record player.

If the Internet is to be believed, Baby Boomers spent much of their youth rewinding audio cassettes with pencils. Cassette recorders were revolutionary in that they combined portability with the ability to customise content. It was now possible to create compilations of music from the radio, records or other tapes and take them with you. Add to this a compact amplifier and high-quality headphones and the Walkman is born. You can now create the soundtrack to your life, and listen to it as you jog or roller-skate around carrying a backpack full of cassettes.

The VCR brought the same customisability, though not the portability, to video content. You could now record your favourite shows to watch at leisure. You could do this even if you weren’t at home, provided you were one of the few people on the planet who knew how to programme a VCR. This, combined with cable TV and niche global channels, shaped the MTV Generation.

The converging trends towards customisability, portability and individualisation have led inexorably to the digital and mobile revolutions. Now, we can access all the content we want, wherever we want and experience it alone if we want.

Now, we can access all the content we want, wherever we want and experience it alone if we want.

Each of these technological advances, and its eager adoption by the youth of the day, caused concern to older generations.

Television, it was believed, would turn Gen X-ers into couch potatoes unable to relate to other people or do a decent day’s work. As people from the Generation X cohort went on to become the most entrepreneurial generation ever, attention has moved to the much maligned millennials. They — we are told — relate more to screens and less to people. They are addicted to social media, and crave the instant gratification of the like, expecting constant praise for everything they do.

The Boomers’ passion — rock and roll – was condemned by many as a communist plot to subvert the morality of youth through its use of ‘jungle beats’ (astute readers may detect an element of racism creeping in here).

This was part of the wider scourge of radio. The music magazine Gramophone warned in 1936 that radio would dumb down the GI Generation by distracting children from their school work. Which excitable young mind could resist the habit “of dividing attention between the humdrum preparation of their school assignments and the compelling excitement of the loudspeaker”.

At least the radio kept kids away from newspapers: a heinous 18th century fad which, according to Malesherbes, socially isolated readers and detracted from the spiritually uplifting group practice of getting news from the church pulpit.

Information overload and its effects on the young mind are a common theme in intergenerational technophobia. Respected Swiss scientist Conrad Gessner describes how the modern world overwhelms people with information and that this overabundance is both “confusing and harmful” to the mind. Gessner would have loathed the internet, had he not died of the plague in 1564. He was bemoaning the flood of information released by the invention of the printing press.

Conrad Gessner describes how the modern world overwhelms people with information and that this overabundance is both “confusing and harmful” to the mind.

If printing was bad, how about writing? Socrates, in the 4th century BC warned it would “create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories.”

I’m sure Socrates didn’t invent this cycle of concern, however. I can well imagine our cave-dwelling ancestors railing against the younger generation’s obsession with new-fangled innovations like fire and the wheel.

One of the keys to successfully working across generations is to break the cycle and reject the myths. We need to concentrate far more on what we have in common than what divides us.

Many of the behaviours associated with younger generations, both now and 2,500 years ago, are general features of youth rather than traits of specific generations. Before complaining about teenagers spending every waking hour texting or snapchatting their friends, remember when your parents put in an extra landline to cope with your unending phone calls. The behaviour is the same, it’s just the medium which is different.

The idea that each technological advance affects only younger people is also a myth.

1950s transistor radios didn’t just play Elvis. They also provided the soundtrack to family picnics and retirees’ fishing trips. My grandparents watched far more TV than I ever did or will. For every sexting shapchatter there is someone sharing grandkid pics on their smartphone.

Older people may not embrace new technology with the enthusiasm and obsession of youth, partly because they don’t have the time, the need or the peer pressure. They doesn’t mean they are less able to do so. I reject the concept of digital natives. My granddaughter has been using an iPad since she was three. Does that mean she’ll be better at designing spreadsheets than anyone else? I think not necessarily.

Technology enables us to communicate much better than ever before. We should not let myths about it making us different divide us. Instead, we should focus on what we have in common.

Now please skype, text, IM or talk to someone from a different generation, or culture from you. Delight in your difference, and celebrate what you share.