Black History Month – expanding the narrative

Black History Month is celebrated in February in the United States and Canada, and in October in the UK and the Netherlands.

Beyond slavery, oppression and a nice lady on a bus

I am struck by how many accounts focus on the history of black people in the United States to the exclusion of the rest of the world. They are almost exclusively about passivity and victimhood, ended by the actions of charismatic individuals. These heroes are then sanitized for public consumption. Rosa Parks, the tireless campaigner for civil rights, had been the only woman on the board of her local NAACP for 13 years before she boarded the bus. She had organized the defense of black men wrongly accused of rape and campaigned for justice for a black rape survivor. She went on to be active in the Black Power movement and to campaign of behalf of political prisoners. She was adamant that the struggle for justice was not over. She was far more than a lady on a bus who refused to give up her seat.

Slavery, exploitation, segregation, voter suppression, mass incarceration, bias and discrimination should not be ignored or papered over, but they are not the only story.

Defining black history as about the people of Sub-Saharan Africa and those with African ancestry around the world, I set out to explore what I didn’t know. That, of course, was most of it!

10,000 nations, vast empires and great cities

Africa is of course where human history begins, with the evolution of modern humans and the great migrations around and out of the continent.

This internal isolation started to change when the Bantu-speaking people of what is now Cameroon began to develop agriculture and to use iron and ceramics in around 2000 BC. This enabled them to exploit the tropical savannas covering much of the continent, and they began an expansion that would take them first into East Africa by 1000 BC, then into Southern Africa, reaching KwaZulu-Natal by 300 AD. Bantu languages, such as Swahili, Kikuyu, Zulu, Xhosa and 500 more, are today spoken across vast areas of the continent.

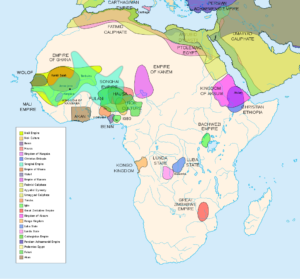

West Africa was home to a succession of empires, with the territory of each one expanding and overlapping its predecessor. The Ghana empire flourished between the 9th and 12th centuries AD and was superseded by the Mali empire, which expanded north into the Sahara, west to the Atlantic and east as far as the Niger bend. The great city of Timbuktu was developed as a center of trade and learning. The empire enjoyed great wealth. When the emperor of Mali, Mansa Musa (1312–1337) undertook the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, he took so much wealth with him that the price of gold in the Arab world slumped for a decade.

The Oyo empire was one of the largest West African states into the late 18th Century.

Meanwhile, the Bantu people founded port cities along the East African coast and Great Zimbabwe, further south, home to the largest stone structures south of the Sahara. Great cosmopolitan cities such as Mombasa, Zanzibar and Kilwa traded with the Arab world, Persia, India and China.

European imperialism and the scramble for Africa

By the 1870s, over 10,000 sovereign states existed on the African continent – each with distinct languages and cultures. This was set to change very drastically. The invention of the machine gun enabled European armies to overcome African resistence – even the all-woman regiment known as the Dahomey Amazons who held back a French invading force . The discovery of quinine for protection against malaria enabled Europeans to colonize the continent. In the twenty years between 1878 and 1898, European states conquered the whole continent, with the sole exceptions of Liberia and Ethiopia. To avoid war between themselves, the Europeans divided up the continent between them at the Berlin Conference in 1884. The so-called ‘scramble for Africa’ resulted in arbitrary colonies and territories with no reference to historical and cultural factors.

Independent once more

The European occupation of Africa lasted for between 50 and 100 years. 1960 was known as the Year of Africa, when 17 new countries gained independence. Zimbabwe, the last colony, became independent form the UK in 1980.

New leaders emerged onto the continent and world stage. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal were among the founders of the non-aligned movement. The Organization of African Unity was formed, which some hoped would lead to a united federal African nation.

Women leaders

Women have played a key role in the post-colonial leadership. The first elected female head of state in Africa was Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, President of Liberia. Senegal has had two female prime ministers and one president, while Guinea Bissau has had one PM and one president. Mozambique, Rwanda and Namibia also boast female prime ministers while another woman president has served in Malawi. Gender equality in Rwanda was rated sixth-best in the world by the World Economic Forum in 2015. It was the first country in the world to have a majority of female law makers, with 61.3% of parliamentary seats occupied by women in 2015.

Out of Africa

Around 140 million people with African ancestry live outside the continent of Africa. Many members of the African diaspora have ancestors who were dispersed throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia as victims of the Atlantic and Arab slave trades – the largest forced migration in human history. The largest populations of black people outside Africa are in Brazil, the United States, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Colombia.

Haiti has a very special place in black history. On January 1, 1804 Haiti became the first independent nation in Latin America and the Caribbean and the second republic in the Americas. This was the result of a successful anti-slavery and anti-colonial uprising by enslaved people who liberated themselves. A nation founded and run by black people challenged long-held beliefs about supposed black inferiority.

Not everyone who left Africa did so against their will. A recent book by historian Miranda Kaufmann tells the stories of black people in Tudor England. These include John Blanke, a court trumpeter who performed at Henry VII’s funeral and Henry VIII’s coronation in 1509, and Jacques Francis a salvage diver. Francis became the first African to give evidence in an English court of law.

Black Britain

In modern times, around 3.5 million Africans have migrated mainly to Europe. Although the history of black people in the UK goes back to Roman times, the first large increase in the community happened after the first world war with merchant seamen from the Caribbean settling in port cities. There were also small numbers of students from Africa and the Caribbean. World War II also marked a period of growth in black communities in the UK, as workers and servicemen from the West Indies arrived in the country.

A ship called the Empire Windrush was involved in a significant event in Black British history. En route from Australia to England via the Atlantic in 1948, the ship stopped in Kingston, Jamaica, to pick up servicemen returning to the UK. The British Nationality Act had just been passed giving citizens of British colonies the automatic right to work and settle in the UK. Since the ship was far from full, advertisements were placed in the Jamaican press offering cheap tickets. Many people took the trip out of curiosity to see what England was like. 492 Jamaicans arrived at the port of Tilbury, near London. They were initially housed in an underground shelter in Clapham, South London, less that a mile from and Employment Exchange in Brixton where many of them found work. Although some people returned to Jamaica, the majority settled in London founding the vibrant Afro-Caribbean community centered on Brixton.

What next?

These are just a few of the many stories that do not figure in the standard narrative about black people. Ignoring and denying black history is part of the institutionalized racism that blights all our lives. We all need to do more to educate ourselves about the history of 1/7 of humanity.